Kanalcodierung/Definition und Eigenschaften von Reed–Solomon–Codes: Unterschied zwischen den Versionen

Ayush (Diskussion | Beiträge) (Die Seite wurde neu angelegt: „ {{Header |Untermenü=Reed–Solomon–Codes und deren Decodierung |Vorherige Seite=Erweiterungskörper |Nächste Seite=Reed–Solomon–Decodierung beim Ausl…“) |

Ayush (Diskussion | Beiträge) |

||

| Zeile 8: | Zeile 8: | ||

== Konstruktion von Reed–Solomon–Codes (1) == | == Konstruktion von Reed–Solomon–Codes (1) == | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | Ein | + | Ein <b>Reed–Solomon–Code</b> – im Folgenden manchmal auch verkürzt als RS–Code bezeichnet – ist ein linearer Blockcode, der einem Informationsblock <u><i>u</i></u> mit <i>k</i> Symbolen ein entsprechendes Codewort <u><i>c</i></u> mit <i>n</i> > <i>k</i> Symbolen zuordnet. Diese noch heute vielfach eingesetzten Codes wurden bereits Anfang der 1960er Jahre von Irving Stoy Reed und Gustave Solomon erfunden.<br> |

[[Datei:P ID2515 KC T 2 3 S1 v2.png|Linearer (<i>n</i>, <i>k</i>)–Blockcode|class=fit]]<br> | [[Datei:P ID2515 KC T 2 3 S1 v2.png|Linearer (<i>n</i>, <i>k</i>)–Blockcode|class=fit]]<br> | ||

| Zeile 38: | Zeile 38: | ||

*Meist werden die Codesymbole <i>c<sub>i</sub></i> ∈ GF(2<sup><i>m</i></sup>) vor der Übertragung wieder in Binärform ⇒ GF(2) gebracht, wobei dann jedes Symbol durch <i>m</i> Bit dargestellt wird.<br> | *Meist werden die Codesymbole <i>c<sub>i</sub></i> ∈ GF(2<sup><i>m</i></sup>) vor der Übertragung wieder in Binärform ⇒ GF(2) gebracht, wobei dann jedes Symbol durch <i>m</i> Bit dargestellt wird.<br> | ||

| + | == Konstruktion von Reed–Solomon–Codes (2) == | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | Fassen wir die Aussagen der letzten Seite kurz zusammen: | ||

| + | {{Definition}}''':''' Ein (<i>n</i>, <i>k</i>)–Reed–Solomon–Code für das Galoisfeld GF(2<sup><i>m</i></sup>) wird festgelegt durch | ||

| + | *die <i>n</i> = 2<sup><i>m</i></sup>–1 Elemente von GF(2<sup><i>m</i></sup>)\{0} = {<i>α</i><sup>0</sup>, <i>α</i><sup>1</sup>, ... , <i>α</i><sup><i>n</i>–1</sup>}, wobei <i>α</i> ein <b>primitives Element</b> von GF(2<sup><i>m</i></sup>) bezeichnet, | ||

| + | *ein an den Informationsblockt <u><i>u</i></u> angepasstes <b>Polynom</b> vom Grad <i>k</i>–1 der Form | ||

| + | ::<math>u(x) = \sum_{i = 0}^{k-1} u_i \cdot x^{i} = u_0 + u_1 \cdot x + u_2 \cdot x^2 + \hspace{0.1cm}... \hspace{0.1cm}+ u_{k-1} \cdot x^{k-1} \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.4cm} u_i \in {\rm GF}(2^m) | ||

| + | \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| + | Damit lässt sich der <b>(<i>n</i>, <i>k</i>)–Reed–Solomon–Code</b> beschreiben als | ||

| + | :<math>C_{\rm RS} = \Big \{ \underline {c} = \big ( u(\alpha^{0}) \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.1cm} u(\alpha^{1})\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.1cm}...\hspace{0.1cm}, u(\alpha^{n-1})\hspace{0.1cm} \big ) | ||

| + | \hspace{0.1cm} \big | \hspace{0.2cm} u(x) = \sum_{i = 0}^{k-1} u_i \cdot x^{i}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} u_i \in {\rm GF}(2^m) | ||

| + | \Big \} \hspace{0.05cm}.</math>{{end}}<br> | ||

| + | Die bisherigen Angaben sollen nun an einem einfachen Beispiel verdeutlicht werden. | ||

| + | {{Beispiel}}''':''' Wir gehen von den folgenden Codeparametern aus: | ||

| + | :<math>k = 2 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.15cm}n = 3 \hspace{0.5cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.5cm} \underline {u} = (u_0, u_1)\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.15cm} | ||

| + | \underline {c} = (c_0, c_1, c_2)\hspace{0.05cm},</math> | ||

| + | :<math>q = n+1 = 4 \hspace{0.45cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.5cm} {\rm GF} (q) = {\rm GF} (2^m) | ||

| + | \hspace{0.5cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.5cm} m = 2\hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

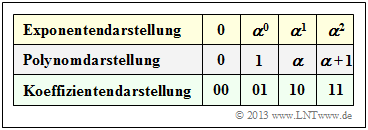

| + | Ausgehend von der Bedingungsgleichung <i>p</i>(<i>α</i>) = <i>α</i><sup>2</sup> + <i>α</i> + 1 = 0 ⇒ <i>α</i><sup>2</sup> = <i>α</i> + 1 erhält man folgende Zuordnungen zwischen der Exponenten–, der Polynom– und der Koeffizientendarstellung von GF(2<sup>2</sup>):<br> | ||

| + | [[Datei:P ID2517 KC T 2 3 S1b v3.png|GF(2<sup>2</sup>) in Exponenten–, Polynom– und Koeffizientenform |class=fit]]<br> | ||

| + | Der Koeffizientenvektor wird durch das Polynom <i>u</i>(<i>x</i>) = <i>u</i><sub>0</sub> + <i>u<sub>i</sub></i> · <i>x</i> ausgedrückt. Der Polynomgrad ist <nobr><i>k</i> – 1 = 1.</nobr> Für <i>u</i><sub>0</sub> = <i>α</i><sup>1</sup> und <i>u</i><sub>1</sub> = <i>α</i><sup>2</sup> erhält man beispielsweise das Polynom <i>u</i>(<i>x</i>) = <i>α</i> + <i>α</i><sup>2</sup> · <i>x</i> und damit | ||

| + | :<math>c_0 \hspace{-0.15cm} = \hspace{-0.15cm} u (x = \alpha^0) = u (x = 1) = \alpha + \alpha^2 \cdot 1 = \alpha + (\alpha + 1) =1 \hspace{0.05cm},</math> | ||

| + | :<math>c_1 \hspace{-0.15cm} = \hspace{-0.15cm} u (x = \alpha^1) = \alpha + \alpha^2 \cdot \alpha = \alpha + \alpha^3 = \alpha + \alpha^0 = \alpha + 1 = \alpha^2 \hspace{0.05cm},</math> | ||

| + | :<math>c_2 \hspace{-0.15cm} = \hspace{-0.15cm} u (x = \alpha^2) = \alpha + \alpha^2 \cdot \alpha^2 = \alpha + \alpha^4 = \alpha + \alpha^1 = 0 \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| + | Daraus ergeben sich folgende Zuordnungen auf Symbol– bzw. Bitebene: | ||

| + | :<math>\underline {u} \hspace{-0.15cm} = \hspace{-0.15cm} (\alpha^1, \alpha^2)\hspace{0.57cm}\leftrightarrow\hspace{0.3cm} | ||

| + | \underline {c} = (1, \alpha^2, 0)\hspace{0.05cm},</math> | ||

| + | :<math>\underline {u}_{\rm bin} \hspace{-0.15cm} = \hspace{-0.15cm} (1,0,1,1)\hspace{0.3cm}\leftrightarrow\hspace{0.3cm} | ||

| + | \underline {c}_{\rm bin} = (0,1,1,1,0,0)\hspace{0.05cm}.</math>{{end}}<br> | ||

| + | == Konstruktion von Reed–Solomon–Codes (3) == | ||

| + | <br> | ||

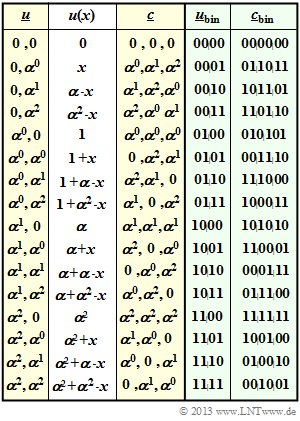

| + | Die folgende Grafik zeigt die Codetabelle dieses RSC (3, 2, 2)<sub>4</sub> genannten Reed–Solomon–Codes. Die Bezeichnung bezieht sich auf die Parameter <i>n</i> = 3, <i>k</i> = 2, <i>d</i><sub>min</sub> = 2 und <i>q</i> = 4. In den Spalten 1 bis 3 erkennt man den Zusammenhang <u><i>u</i></u> → <i>u</i>(<i>x</i>) → <u><i>c</i></u>, in den beiden letzten die Codiervorschrift <u><i>u</i></u><sub>bin</sub> ↔ <u><i>c</i></u><sub>bin</sub>.<br> | ||

| + | [[Datei:P ID2570 KC T 2 3 S1bb v3.png|rahmenlos|rechts|Codetabelle des RSC (3, 2, 2)<sub>4</sub>]] | ||

| + | <br><br><br> | ||

| + | Zur Verdeutlichung nochmals der Eintrag für (<i>α</i><sup>0</sup>, <i>α</i><sup>2</sup>): | ||

| + | :<math>u(x) = u_0 + u_1 \cdot x = \alpha^0 + \alpha^2 \cdot x. </math> | ||

| + | Daraus ergeben sich folgende Codesymbole: | ||

| + | :<math>c_0 \hspace{-0.15cm} = \hspace{-0.15cm} u (x = \alpha^0) = 1 + \alpha^2 \cdot 1 =</math> | ||

| + | :<math> = \hspace{-0.15cm}1 + (1+\alpha ) =\alpha \hspace{0.05cm},</math> | ||

| + | :<math>c_1 \hspace{-0.15cm} = \hspace{-0.15cm} u (x = \alpha^1) = 1 + \alpha^2 \cdot \alpha =</math> | ||

| + | :<math> = \hspace{-0.15cm}1 + (1+\alpha ) \cdot \alpha = 1 + \alpha + \alpha^2 = 0 \hspace{0.05cm},</math> | ||

| + | :<math>c_2 \hspace{-0.15cm} = \hspace{-0.15cm} u (x = \alpha^2) = 1 + \alpha^2 \cdot \alpha^2 =</math> | ||

| + | :<math> = \hspace{-0.15cm}1 + \alpha = \alpha^2 \hspace{0.05cm}.</math> | ||

| + | <br><br><br><br><br><br> | ||

| + | <i>Hinweis:</i> Aus der Elementenmenge {0, <i>α</i><sup>0</sup> = 1, <i>α</i><sup>1</sup>, <i>α</i><sup>2</sup>} sollte nicht geschlossen werden, dass für diesen Code die 3D–Darstellung mit den Achsen <i>α</i><sup>0</sup> = 1, <i>α</i><sup>1</sup> und <i>α</i><sup>2</sup> zutrifft. Aus der Koeffizientendarstellung geht vielmehr eindeutig hervor, dass GF(2<sup>2</sup>) ein zweidimensionaler Code ist, wobei die Achsen der 2D–Darstellung mit <i>α</i><sup>0</sup> = 1 und <i>α</i><sup>1</sup> = <i>α</i> zu beschriften sind.<br> | ||

Version vom 13. Januar 2017, 15:06 Uhr

Konstruktion von Reed–Solomon–Codes (1)

Ein Reed–Solomon–Code – im Folgenden manchmal auch verkürzt als RS–Code bezeichnet – ist ein linearer Blockcode, der einem Informationsblock u mit k Symbolen ein entsprechendes Codewort c mit n > k Symbolen zuordnet. Diese noch heute vielfach eingesetzten Codes wurden bereits Anfang der 1960er Jahre von Irving Stoy Reed und Gustave Solomon erfunden.

In Kapitel 1.1 wurde der Informationsblock mit u = (u1, ... , uk) und das Codewort mit x = (x1, ... , xn) bezeichnet. Die Nomenklaturänderung gemäß obiger Grafik wurde vorgenommen, um Verwechslungen mit dem Argument von Polynomen auszuschließen und die Beschreibung der RS–Codes zu vereinfachen.

Alle in Kapitel 1.4 genannten Eigenschaften linearer zyklischer Blockcodes gelten auch für einen Reed–Solomon–Code. Zusätzlich gilt:

- Konstruktion und Decodierung von RS–Codes basieren auf der Arithmetik eines Galoisfeldes GF(q), wobei wir uns hier auf binäre Erweiterungskörper mit q = 2m Elementen beschränken:

- \[{\rm GF}(2^m) = \big \{\hspace{0.05cm}0\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.1cm} \alpha^{0} ,\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.1cm} \alpha^{1}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.1cm} \alpha^{2}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.1cm}...\hspace{0.1cm}, \alpha^{q-2}\hspace{0.05cm} \big \}\hspace{0.05cm}. \]

- Prinzipiell unterschiedlich zum ersten Kapitel ist, dass die Koeffizienten u0, u1, ... , uk–1 nun nicht mehr einzelne Informationsbits (0 oder 1) angeben, sondern ebenfalls Elemente aus GF(2m) sind. Jedes der m Symbole steht vielmehr für m Bit.

- Bei den Reed–Solomon–Codes ist der Parameter n (Codelänge) gleich der Anzahl der Elemente des Galoisfeldes ohne das Nullwort: n = q – 1. Wir verwenden hierzu folgende Nomenklatur:

- \[{\rm GF}(2^m) \hspace{-0.05cm}\setminus \hspace{-0.05cm} \{0\} = \big \{\hspace{0.05cm} \alpha^{0} ,\hspace{0.05cm}\hspace{0.1cm} \alpha^{1}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.1cm} \alpha^{2}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.1cm}...\hspace{0.1cm}, \alpha^{n-1}\hspace{0.05cm} \big \}\hspace{0.05cm}. \]

- Die k Koeffizienten ui ∈ GF(2m) des Informationsblocks u ( 0 ≤ i < k) kann man formal auch durch ein Polynom u(x) ausdrücken. Der Grad des Polynoms ist dabei k–1:

- \[u(x) = \sum_{i = 0}^{k-1} u_i \cdot x^{i} = u_0 + u_1 \cdot x + u_2 \cdot x^2 + \hspace{0.1cm}... \hspace{0.1cm}+ u_{k-1} \cdot x^{k-1} \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.4cm} u_i \in {\rm GF}(2^m) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- Die n Symbole c0, ... , cn–1 des zugehörigen Codewortes c = (c0, c1, ... , cn–1) ergeben sich mit diesem Polynom u(x) zu

- \[c_0 = u(\alpha^{0}) \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.3cm} c_1 = u(\alpha^{1})\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.1cm}...\hspace{0.1cm},\hspace{0.3cm} c_{n-1}= u(\alpha^{n-1}) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

- Meist werden die Codesymbole ci ∈ GF(2m) vor der Übertragung wieder in Binärform ⇒ GF(2) gebracht, wobei dann jedes Symbol durch m Bit dargestellt wird.

Konstruktion von Reed–Solomon–Codes (2)

Fassen wir die Aussagen der letzten Seite kurz zusammen:

- die n = 2m–1 Elemente von GF(2m)\{0} = {α0, α1, ... , αn–1}, wobei α ein primitives Element von GF(2m) bezeichnet,

- ein an den Informationsblockt u angepasstes Polynom vom Grad k–1 der Form

- \[u(x) = \sum_{i = 0}^{k-1} u_i \cdot x^{i} = u_0 + u_1 \cdot x + u_2 \cdot x^2 + \hspace{0.1cm}... \hspace{0.1cm}+ u_{k-1} \cdot x^{k-1} \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.4cm} u_i \in {\rm GF}(2^m) \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

Damit lässt sich der (n, k)–Reed–Solomon–Code beschreiben als

\[C_{\rm RS} = \Big \{ \underline {c} = \big ( u(\alpha^{0}) \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.1cm} u(\alpha^{1})\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.1cm}...\hspace{0.1cm}, u(\alpha^{n-1})\hspace{0.1cm} \big ) \hspace{0.1cm} \big | \hspace{0.2cm} u(x) = \sum_{i = 0}^{k-1} u_i \cdot x^{i}\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.2cm} u_i \in {\rm GF}(2^m) \Big \} \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

Die bisherigen Angaben sollen nun an einem einfachen Beispiel verdeutlicht werden.

\[k = 2 \hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.15cm}n = 3 \hspace{0.5cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.5cm} \underline {u} = (u_0, u_1)\hspace{0.05cm},\hspace{0.15cm} \underline {c} = (c_0, c_1, c_2)\hspace{0.05cm},\]

\[q = n+1 = 4 \hspace{0.45cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.5cm} {\rm GF} (q) = {\rm GF} (2^m) \hspace{0.5cm} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.5cm} m = 2\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

Ausgehend von der Bedingungsgleichung p(α) = α2 + α + 1 = 0 ⇒ α2 = α + 1 erhält man folgende Zuordnungen zwischen der Exponenten–, der Polynom– und der Koeffizientendarstellung von GF(22):

Der Koeffizientenvektor wird durch das Polynom u(x) = u0 + ui · x ausgedrückt. Der Polynomgrad ist <nobr>k – 1 = 1.</nobr> Für u0 = α1 und u1 = α2 erhält man beispielsweise das Polynom u(x) = α + α2 · x und damit

\[c_0 \hspace{-0.15cm} = \hspace{-0.15cm} u (x = \alpha^0) = u (x = 1) = \alpha + \alpha^2 \cdot 1 = \alpha + (\alpha + 1) =1 \hspace{0.05cm},\] \[c_1 \hspace{-0.15cm} = \hspace{-0.15cm} u (x = \alpha^1) = \alpha + \alpha^2 \cdot \alpha = \alpha + \alpha^3 = \alpha + \alpha^0 = \alpha + 1 = \alpha^2 \hspace{0.05cm},\] \[c_2 \hspace{-0.15cm} = \hspace{-0.15cm} u (x = \alpha^2) = \alpha + \alpha^2 \cdot \alpha^2 = \alpha + \alpha^4 = \alpha + \alpha^1 = 0 \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

Daraus ergeben sich folgende Zuordnungen auf Symbol– bzw. Bitebene:

\[\underline {u} \hspace{-0.15cm} = \hspace{-0.15cm} (\alpha^1, \alpha^2)\hspace{0.57cm}\leftrightarrow\hspace{0.3cm} \underline {c} = (1, \alpha^2, 0)\hspace{0.05cm},\]

\[\underline {u}_{\rm bin} \hspace{-0.15cm} = \hspace{-0.15cm} (1,0,1,1)\hspace{0.3cm}\leftrightarrow\hspace{0.3cm} \underline {c}_{\rm bin} = (0,1,1,1,0,0)\hspace{0.05cm}.\]

Konstruktion von Reed–Solomon–Codes (3)

Die folgende Grafik zeigt die Codetabelle dieses RSC (3, 2, 2)4 genannten Reed–Solomon–Codes. Die Bezeichnung bezieht sich auf die Parameter n = 3, k = 2, dmin = 2 und q = 4. In den Spalten 1 bis 3 erkennt man den Zusammenhang u → u(x) → c, in den beiden letzten die Codiervorschrift ubin ↔ cbin.

Zur Verdeutlichung nochmals der Eintrag für (α0, α2):

\[u(x) = u_0 + u_1 \cdot x = \alpha^0 + \alpha^2 \cdot x. \]

Daraus ergeben sich folgende Codesymbole:

\[c_0 \hspace{-0.15cm} = \hspace{-0.15cm} u (x = \alpha^0) = 1 + \alpha^2 \cdot 1 =\] \[ = \hspace{-0.15cm}1 + (1+\alpha ) =\alpha \hspace{0.05cm},\] \[c_1 \hspace{-0.15cm} = \hspace{-0.15cm} u (x = \alpha^1) = 1 + \alpha^2 \cdot \alpha =\] \[ = \hspace{-0.15cm}1 + (1+\alpha ) \cdot \alpha = 1 + \alpha + \alpha^2 = 0 \hspace{0.05cm},\] \[c_2 \hspace{-0.15cm} = \hspace{-0.15cm} u (x = \alpha^2) = 1 + \alpha^2 \cdot \alpha^2 =\] \[ = \hspace{-0.15cm}1 + \alpha = \alpha^2 \hspace{0.05cm}.\]

Hinweis: Aus der Elementenmenge {0, α0 = 1, α1, α2} sollte nicht geschlossen werden, dass für diesen Code die 3D–Darstellung mit den Achsen α0 = 1, α1 und α2 zutrifft. Aus der Koeffizientendarstellung geht vielmehr eindeutig hervor, dass GF(22) ein zweidimensionaler Code ist, wobei die Achsen der 2D–Darstellung mit α0 = 1 und α1 = α zu beschriften sind.